As computers are used widely, linear algebra becomes more and more powerful even in comparison to calculus. In fact, the combination of the two begets differential geometry, which is essential to Einstein’s general relativity theory.

Following Dr. Grinfelder’s most comprehensive and systematic series, I embark on this journey.

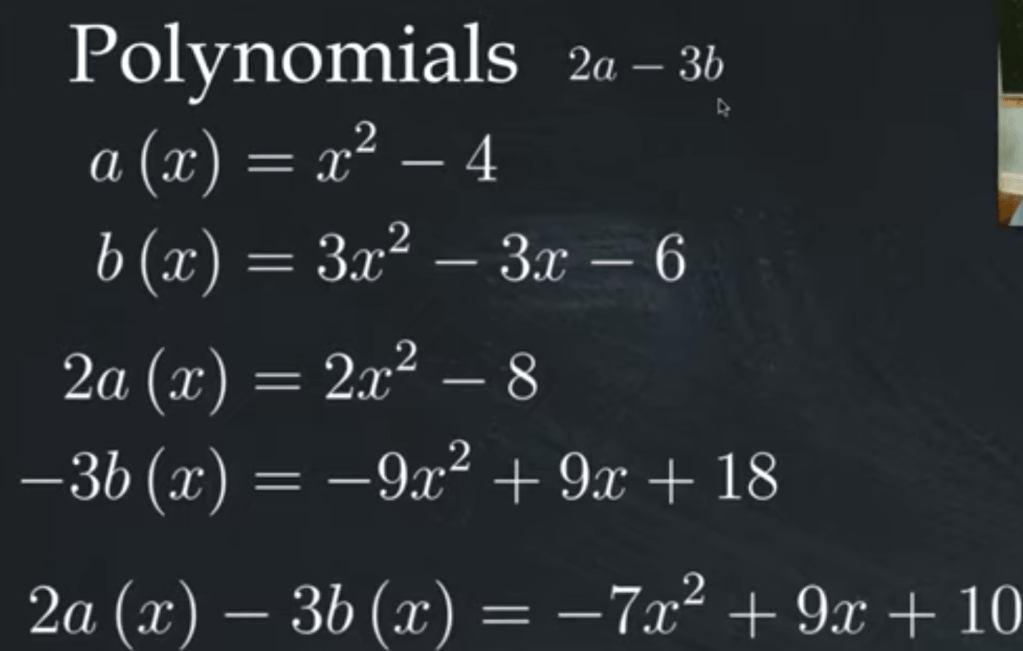

LA is about adding things together in proportions. There are three fundamental kinds of vectors given vectors are the objects that can be added up to form other objects. Audio signals are a practical example. These three kinds look so different but they share the common property – linear. They are Geometric vectors, Polynomials and Rn (Rn is sets of numbers). Rn is the most abstract and hence generic form of vectors.

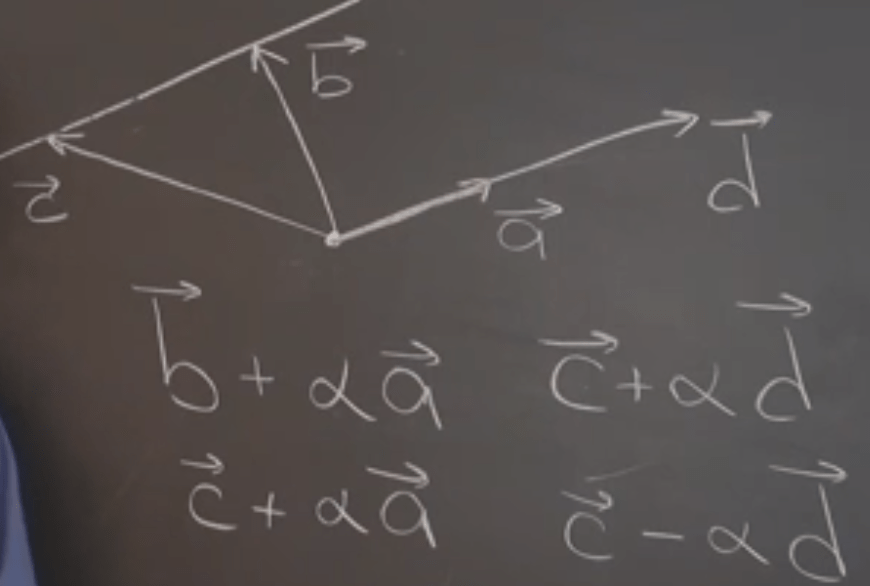

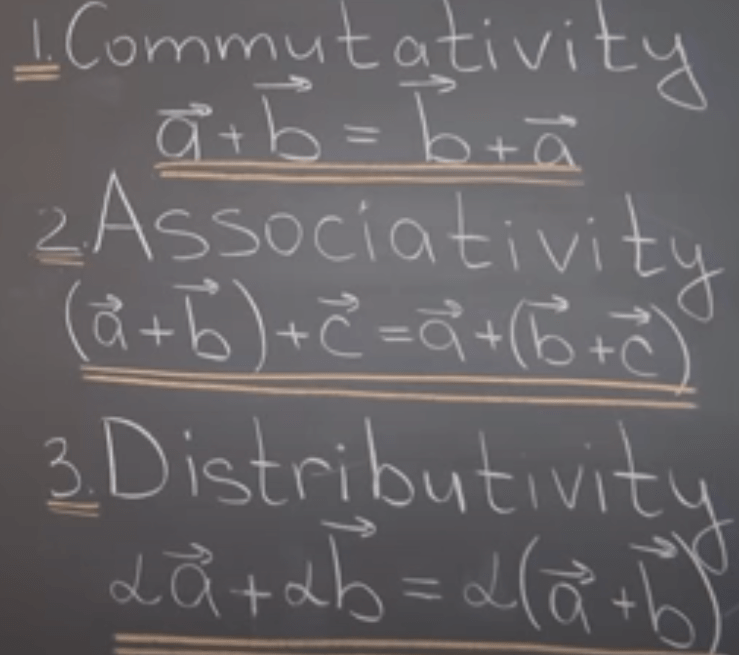

Vectors operates with three properties, commutativity, associativity and distributivity.

As vectors can be floating anywhere, so mathematicians set the Origin in the Plane and the Parallelogram Rule. Parallelogram rule is equivalent to using tip to tail rule. Subtraction is Often Easier than Addition as you just apply tip to tip diff.

What in our life are familiar geometric vectors? – displacements, velocities, accelerations and forces.

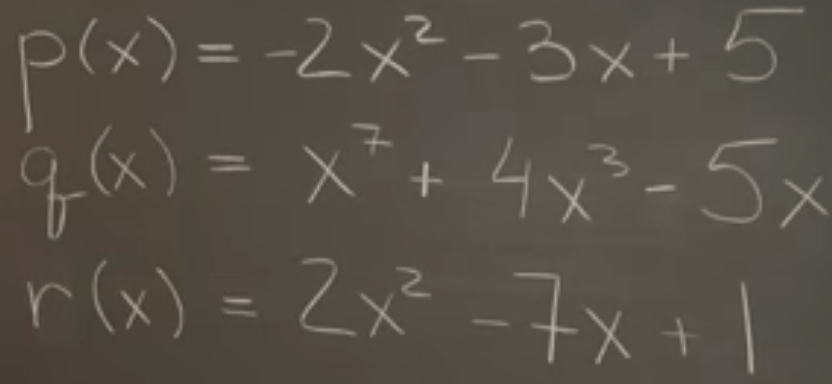

Polynomials or functions, why are they also vectors, they look so different from geometric vectors. but they can also be added, subtracted, scaled. what’s more, they can also similar to vectors can be stuck in a subspace, be stuck too, for example these three polynomials all have root of 1, so they just can’t go away from this below pattern no matter how many scaling, adding or substracting you do.

Rn also shares the same property that no one can escape a subspace if there is a pattern such as the last element is three times the first element.

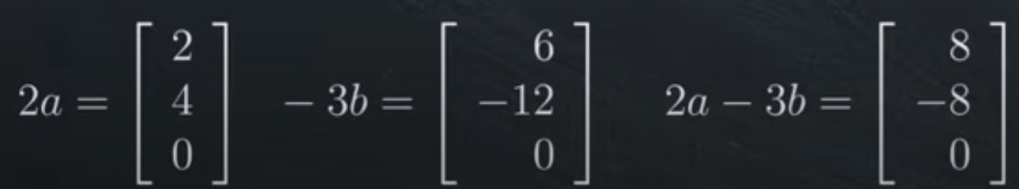

All vectors can do linear combination alpha*a + beta*b, it’s straightforward in geometric vectors, how about polynomials. Note f(2) = 0, so after whichever ways of linear combining, the f(2)=0 still holds.

In set of number form Rn, the property that the third element is zero always holds after linear combination.

In LA, the notion of Span is very important. What is a Span? Span(a, b) = alpha*a + beta*b, indicating all kinds of the combination from a and b, forming a sub-space. You can also call it closure under linear combination. How to prove this is the case? Pick any alpha1, beta1, alpha2, beta2, you can make it look like a number time a plus another number times b, so anyway the new value stuck with the span(a, b). Then we move on to prove the span of polynomials and span of sets of number Rn.

Using two vectors, we can not form a spanning sets of three-dimensional space, however, adding one more vector, if arranged properly, could be. With the same token, can we pick two polynomials as below, and claim they span the quadratic polynomials?

p(x) = 3x^2 + 5x – 8

q(x) = -x^2 + 3x – 2

The answer is no. Both of them has 1 as the root, this property can not break in any circumstances. hence they can not be a spanning set of quadratic.

More examples, the below dots won’t line up if multiplied by a number hence not form a subspace.

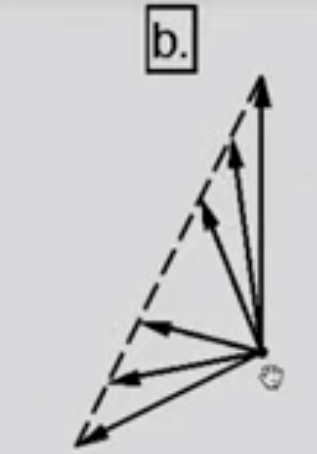

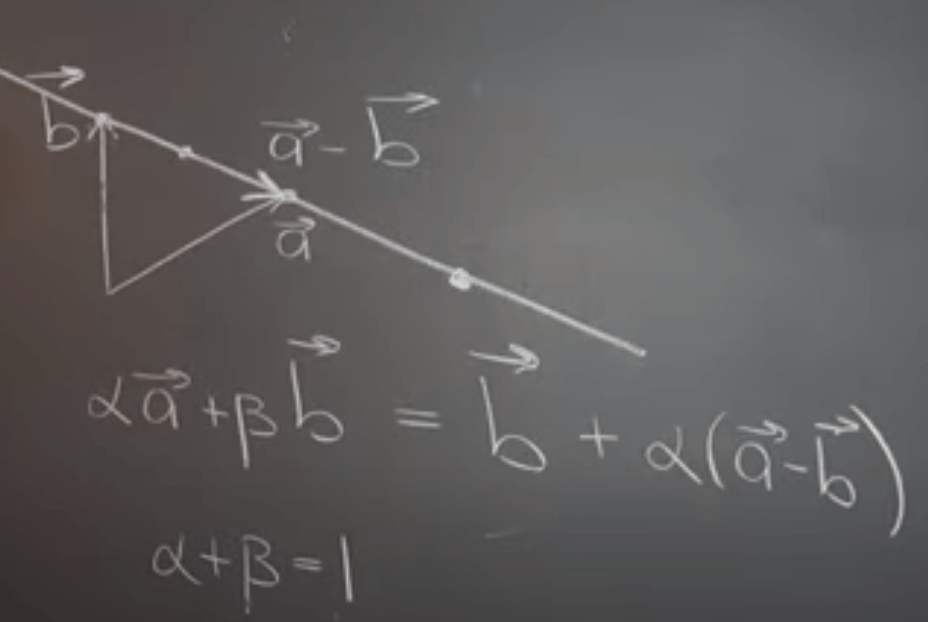

Linear combination with a constraint alpha + beta = 1 leads to an interesting result – the dots form into straight-line.

This is fundamentally important as later further leads to the concept of Null Space and corresponding calculation. To describe a straight line in LA, there are various expressions: