Decomposition: we should not only be content to decompose in cartesian system but any systems. There is a way of thinking borrowing from how a straight line is formed by “b + alpha(b-a)” or alpha*a + beta*b, alpha + beta=1 previously.

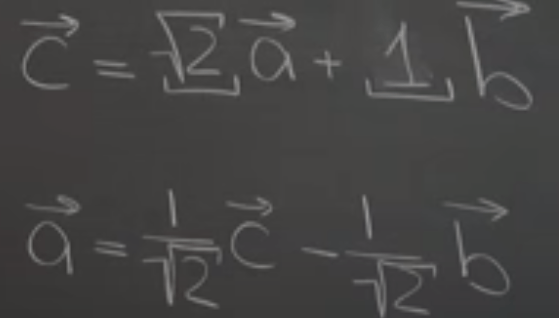

For example, how to get c vector using a and a vectors. It would be difficult at sight but referencing the line bc is parallel to a, so we can write out a = c – b, then scale down from square root of 2 to one.

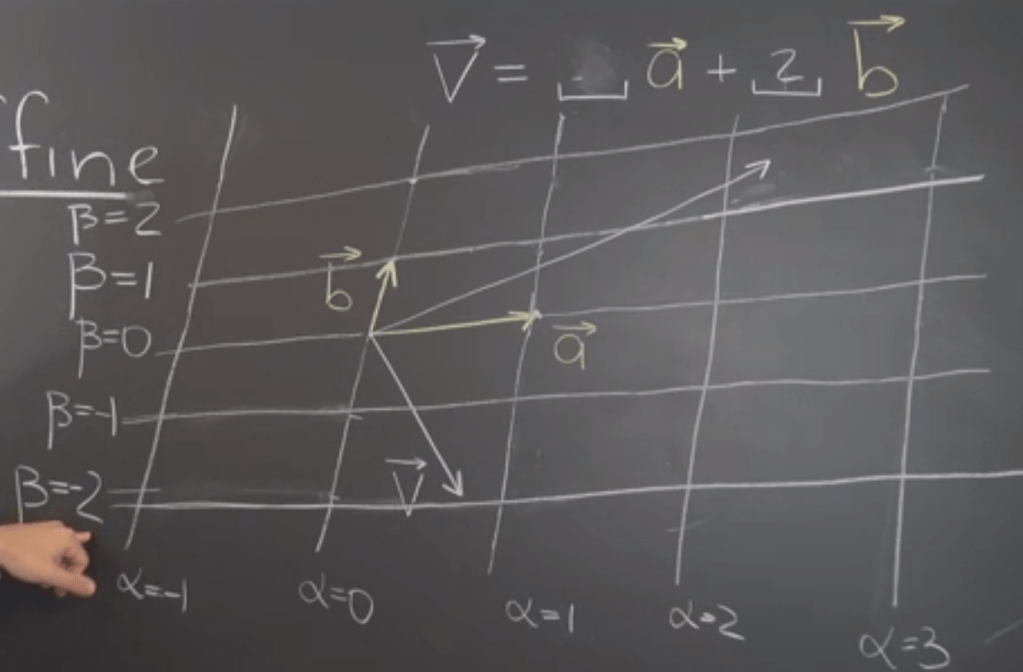

Further, Decomposition with Respect to Arbitrary Geometric Vectors using a robust and generic way – affine grid:

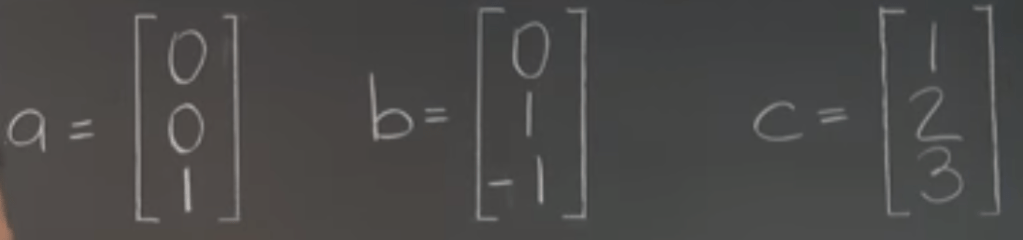

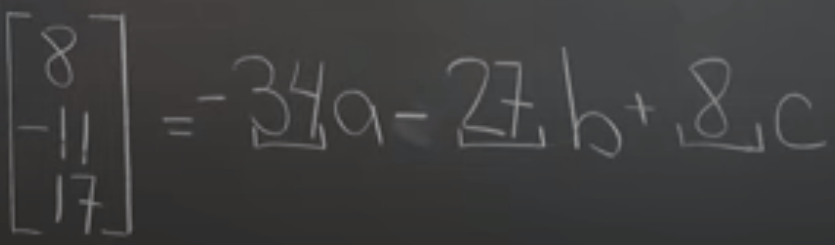

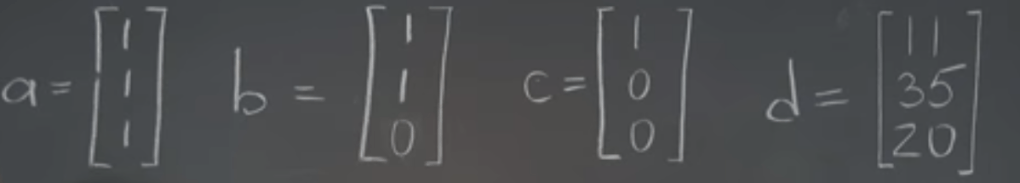

Decomposition of Rn is similar but little bit mind twisting, bearing in mind the bootstrapping approach – start from the most complex base vectors for example in below three bases, start from c

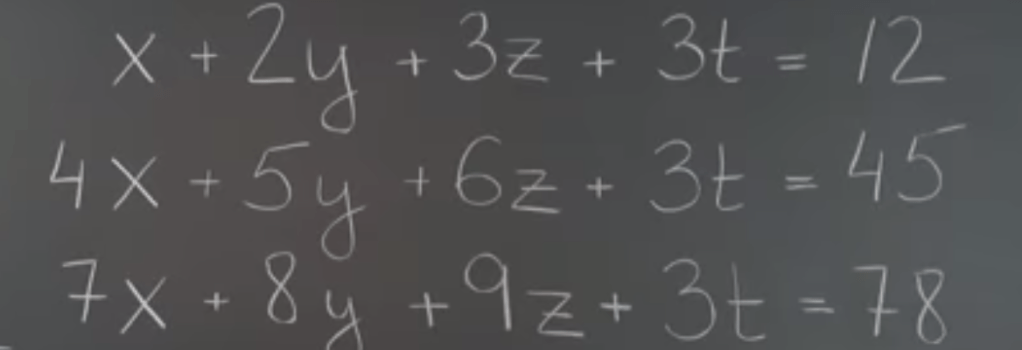

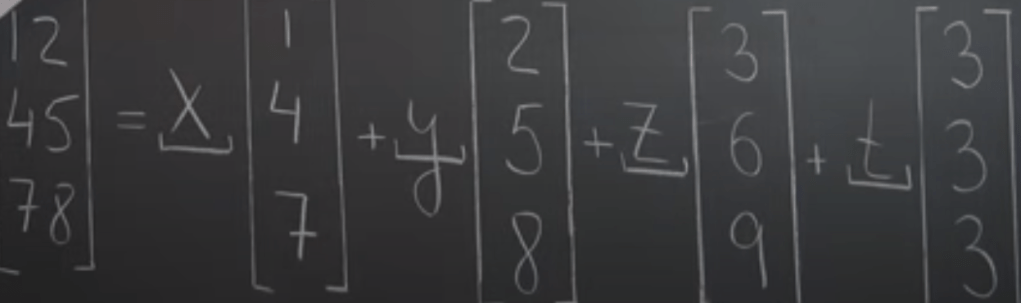

Equipped with this mindset, now we are set ready to solve linear system problems such as

What we are aiming to do is to find four numbers x y z t satisfying the three conditions, it’s equivalent to find the coefficient x y z t that linearly combine the four vectors and form the target vector. It is exact same kind of problem in that Rn decomposition practice.

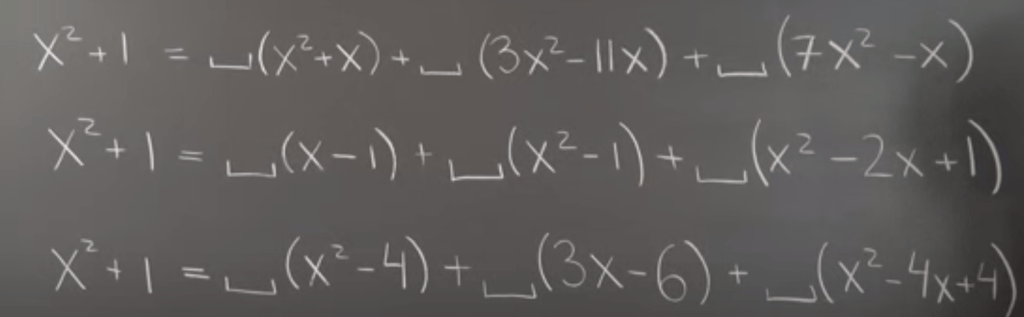

Sometime decomposition doesn’t have any solutions. Sometime decomposition doesn’t have any solutions or have infinite solutions. We say a decomposition problem doesn’t have any solution if the target vector does not stay in the span of the composition vectors. It’s intuitive in geometric vectors, how about polynomials:

It’s the same spirit. in the first equation, a free term is missing in each component, hence the target does not stay in the subspace or the plane of composition part, the second, all coefficients add up to 1 but the target is not, the third, x = 2 is a root for each component, however not in target.

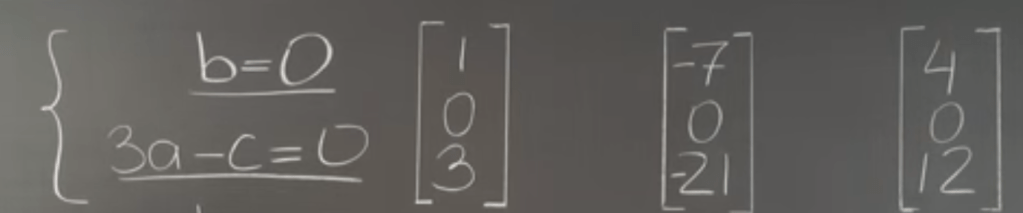

So in sum these vectors need to own a Linear Property: if any linear combination (sum and scale) of these properties(coefficients of Rn) are preserved. And it’s Synonymous with Subspace. For example the below three sets of numbers R3, the linear properties can be expressed in two equations.

Looking into another example of Linear Subspaces of Polynomials: even looks daunting if we apply the closure practice, they are pass the linear property test and hence they are linear.

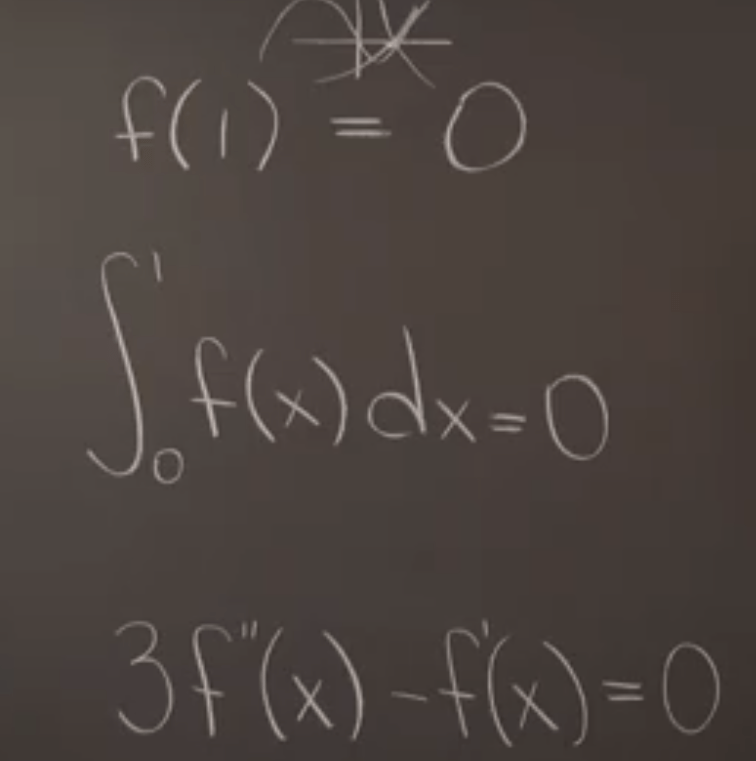

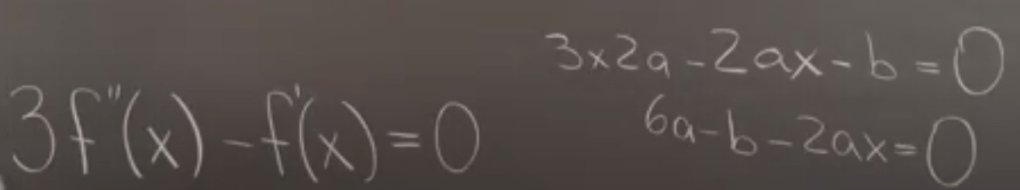

To put into a new, easy to understand format, we can all apply the same f(x) = ax2 + bx + c,

The third one is more tricky

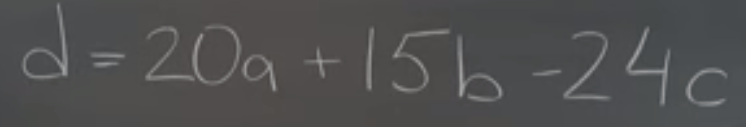

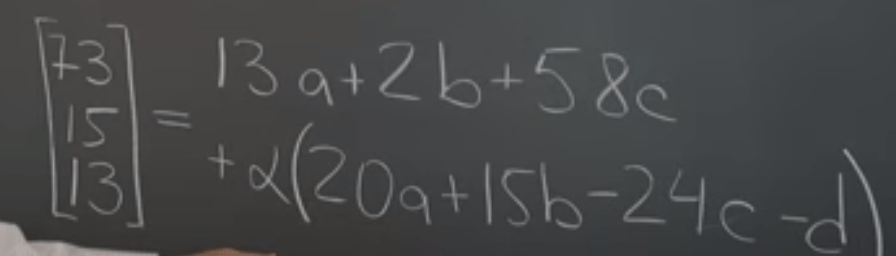

Now introducing a fundamentally important concept linear dependency in LA. There are numerous ways to express vector d in the following given the dependency relationship c = a + b, so a generic way to express is put 2a + b first to form d already, then use alpha to multiply the zero vector (null space, a +b -c).

Linear Dependent (linear property): So a set of vector is linearly dependent if lack of uniqueness, or if there exists at least one of the vectors is a linear combination of the rest. Or a set of vectors is linearly dependent if there exists a nontrivial linear combination that equals zero.

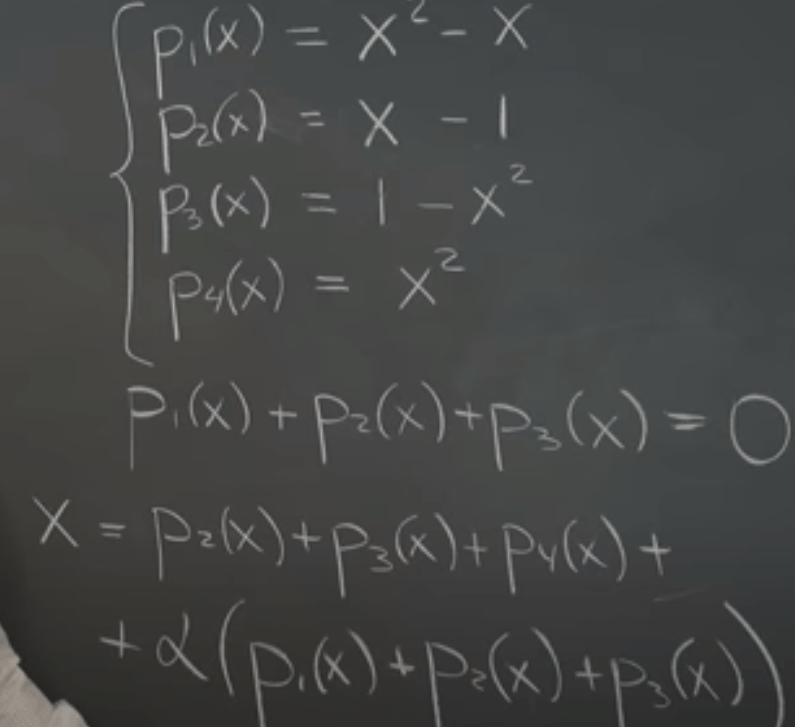

In the same token, we can solve problems of polynomials of Rn using the null space (nontrivial linear combination that equals zero). For example,

While in this set of Rn

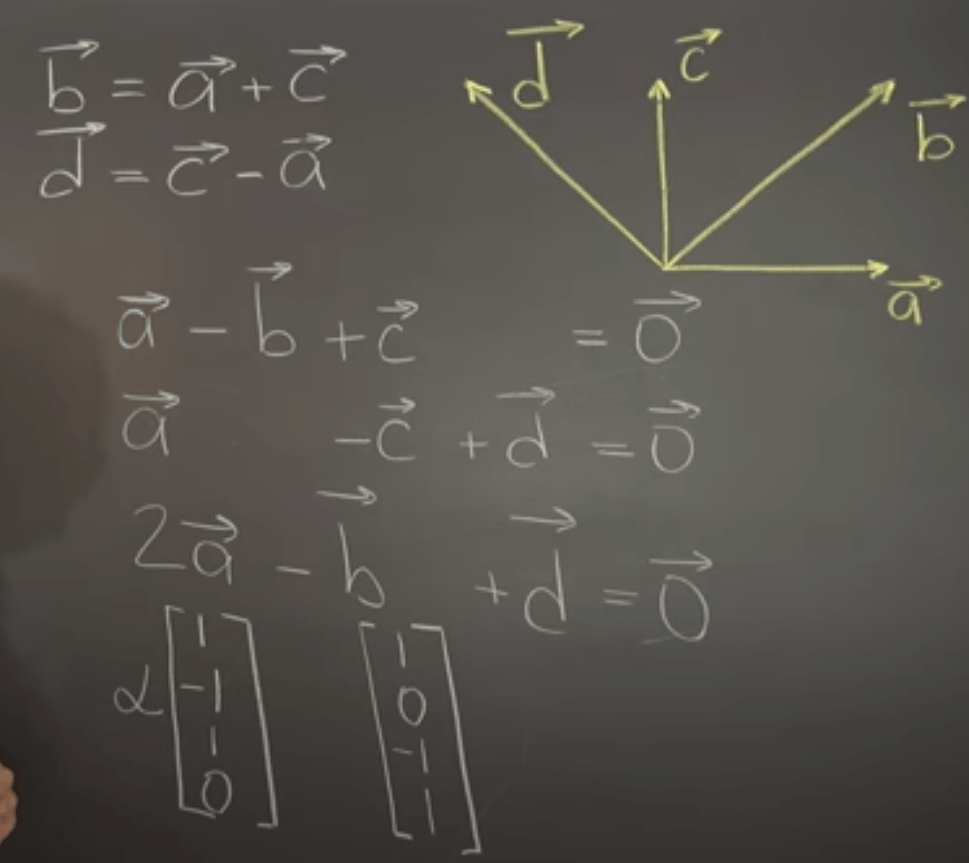

Null Space, linear combination of the linear combinations of vectors forms new subspace in R^(n+1). It’s abstract so here we use an example to illustrate

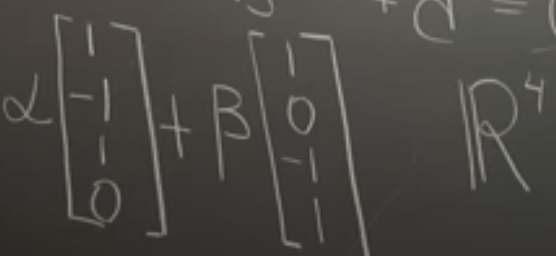

We rearrange the coefficient of the a, b, c, d vectors in R4 form and use alpha times one combination plus beta times another combination: