To thoroughly grasp the concept of a gradient, one needs to think deeply.

First, we must understand that the gradient represents the steepest slope, which can be illustrated with an analogy like standing at a position on a mountain. However, while analogies can be helpful, they are often not rigorous enough. Mathematics, on the other hand, is precise and offers a more robust understanding. There is only one direction that points in the steepest direction of change, but if you’re at the top of a mountain, you might think you can go downhill in any direction. While this may seem true, what you’re missing is that at the top of the mountain, the slope is zero. It’s flat, masking the curvature of the mountain beneath. This is where common sense can confuse the slope we experience in everyday life with the mathematical concept of slope or derivative.

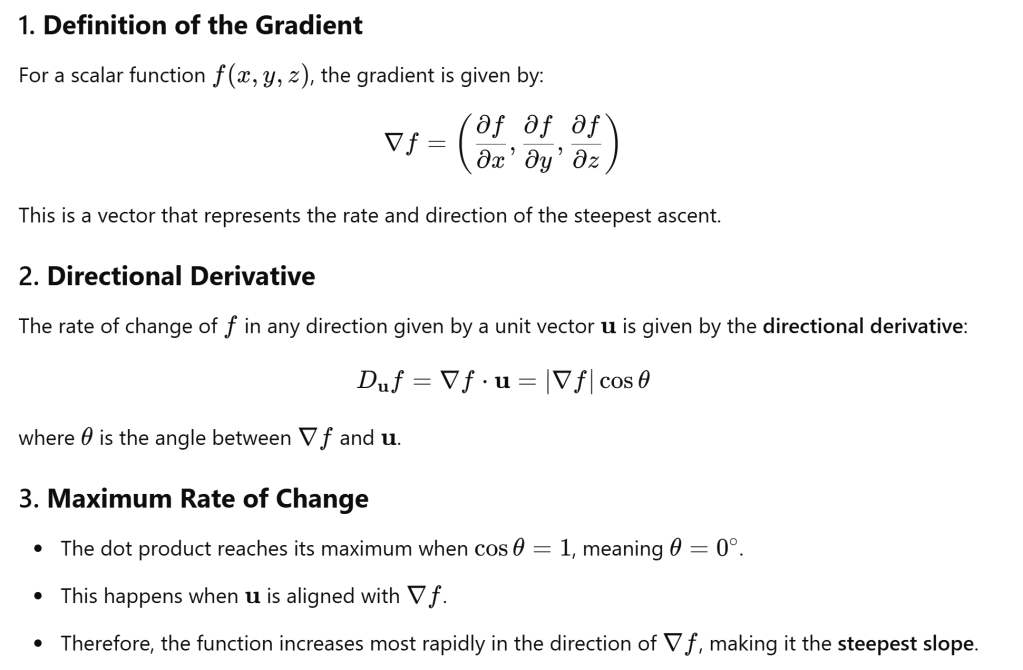

Why gradient is the steepest slope?

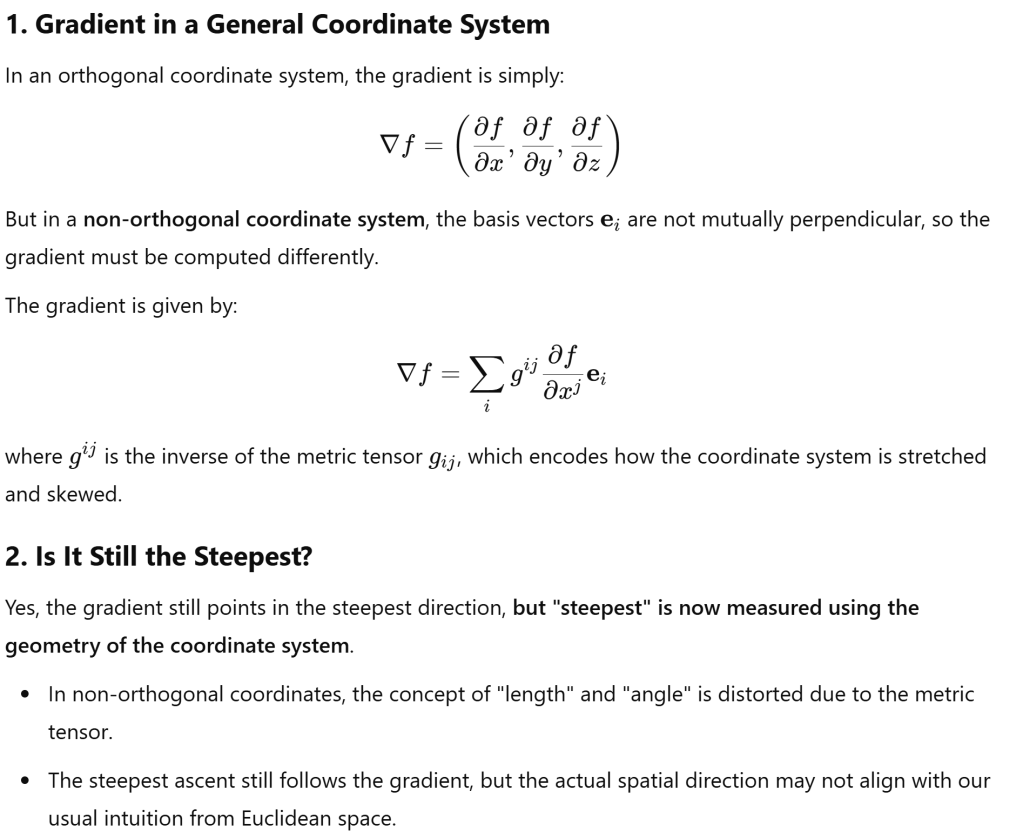

What if x, y z are not orthogonal to each other, is gradient still the steepest?

The reason the gradient remains the steepest ascent is that it is still the vector normal to the level surfaces of f(x,y,z)f(x, y, z)f(x,y,z). The level surfaces (or contour lines) are defined geometrically, independent of the coordinate system. Even though the basis vectors are skewed, the gradient still moves in the fastest-increasing direction, as defined by the underlying space.

On the other hand, it requires deep thought to determine whether the gradient is a vector or a 1-form.