The reason physics and math are difficult for most people is poor teaching. Instead of revealing intuitive concepts—like how homogeneous transformations connect to physical reality or why Hermitian operators represent observables—teachers often overwhelm students with numerous quantum formulas. This makes the subject hard to follow. The right approach is to emphasize intuition and reasoning, which makes learning both fascinating and engaging!

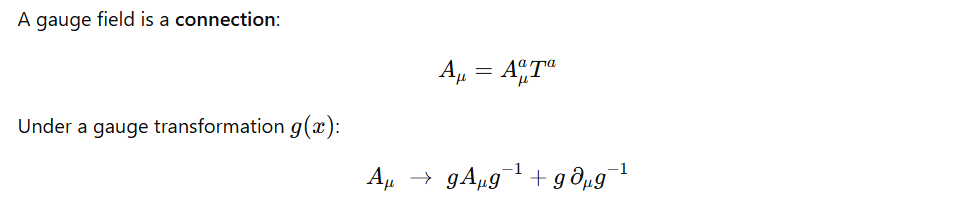

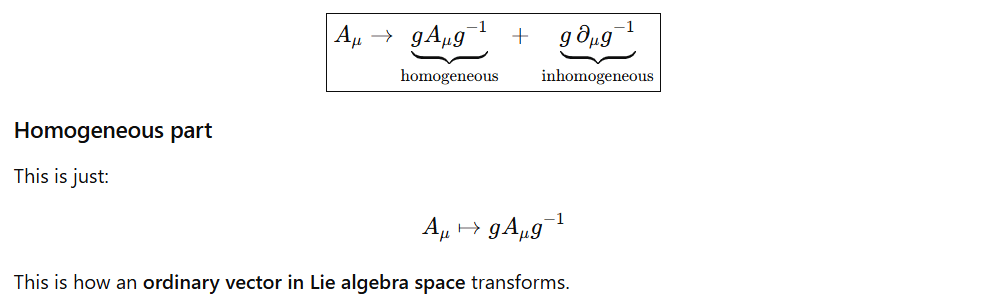

It has homogeneous and inhomegeneous parts:

Because there is another inhomogeneous part of transformation, this Amiu itself is not physical. Why? something that is physical can not vary under reference frame transformation! It’s that simple.

In the same vein, we can understand why, in quantum mechanics, observables are represented by operators. The conceptual leap from classical to quantum physics is that a physical system is no longer described by a single real-valued variable. Instead, it is described by a state vector that encodes many potential measurable quantities—such as energy, position, and momentum—simultaneously.

Experiments show that quantum systems exist in superpositions. When an observation is made, the quantum state must collapse to a definite measurable value of energy, position, or momentum. Mathematically, this act of measurement is represented by applying an operator (a matrix) to the state vector. The eigenvalues of the operator correspond to the possible measured values, and the eigenvectors represent the states the system collapses into.

This is why quantum mechanics does not work with single numerical variables, but with a wavefunction (ψ) that encodes many possible measurement outcomes at once. Because all physical measurements must produce real numbers, the operators representing observables must be Hermitian, which guarantees real eigenvalues and consistent physical predictions.

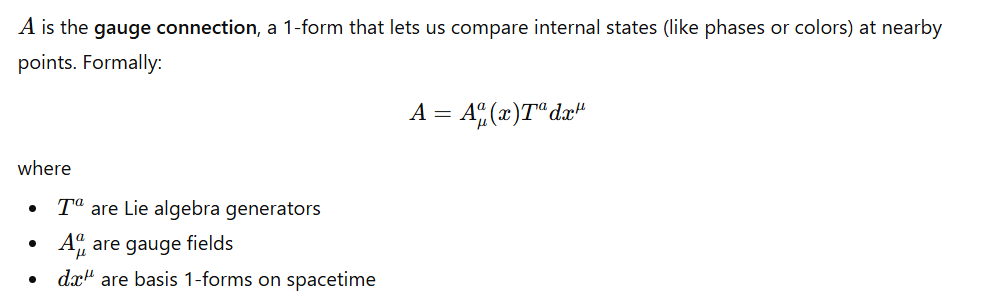

It also reinforce understanding of the curvature F is an invariant because F transform homogeneously. To see that clearly, let’s start from the gauge connection A:

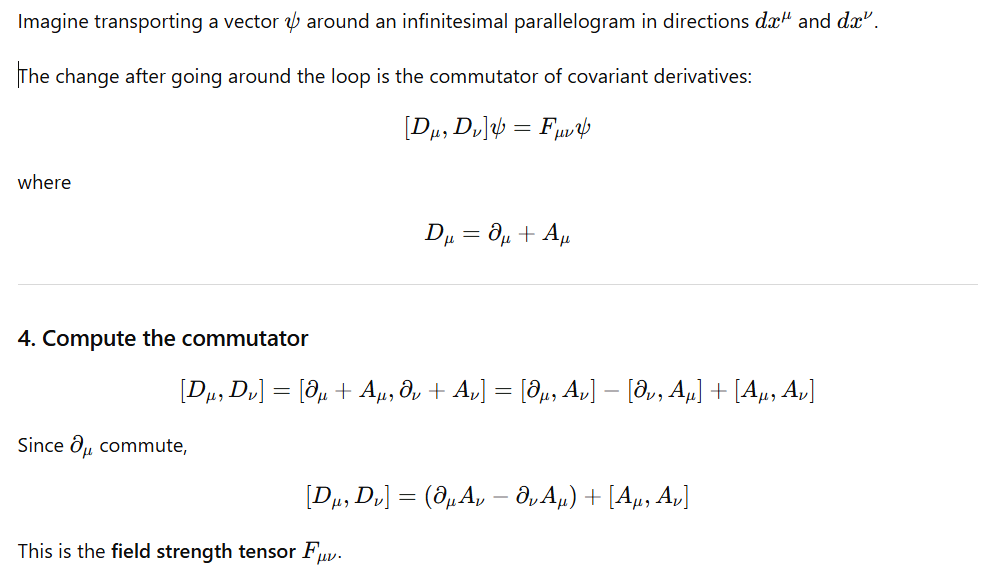

The goal is to measure how much the gauge connection “twists” or “fails to commute” when we move around a small loop in spacetime. This failure to close is called curvature — it encodes the field strength and force.